|

Introduction

This preliminary report presents the results of three excavation seasons conducted at Ramat Rahel between May 2006

and September 2007. For 2005 click here. The first of the three seasons was

financed by KKL and the Israel ministry

of tourism and was dedicated to the excavation of the south-eastern corner of the site (areas D2). Ten hired workmen

worked for three weeks, and the area supervisor was Gilad Cinamon. Other persons Benjamin Arubas (stratigraphical

analysis and surveying), Nirit Shimon, Veronica Zlatkovski, Lior Marom, Boris Babaiev, Shahaf Zach, Amitai Achiman and

Omer Sergey (assistants), and Shrago Pavel (photography).This short preliminary season was quickly followed by a four

weeks excavation season in which an average of 60 team members from Germany, USA and other countries took part.

Four areas were excavated: areas D1, C1 and C2 (excavated already in 2005) and area D3. Staff included Yuval Gadot

(field director), Benjamin Arubas (stratigraphical analysis and surveying), Gilad Cinamon (assistant field director), Liora

Freud (registration), Nirit Shimon, Veronica Zlatkovski, Lior Marom, and Shahaf Zach (area supervisors), Boris Babaiev,

Omer Sergey, Shani Robin and Patricia Grandieri (assistance area supervisors) Amitai Achiman and Carsten Kettering

(Administration), Omer Sergey (team coordinator), Peter van der Veen (academic program), Yoav Pharhi (coins), Itamar

Taxel (pottery analysis) and Pavel Shrago (photography). The third season was held in August 2007, when we

continued excavating areas D1 C1 and C2 and began excavating in area D4. The staff of the 2007 season included Yuval

Gadot (field director), Benjamin Arubas (stratigraphical analysis and surveying), Liora Freud (registration), Nirit Shimon,

Veronica Zlatkovski, Lisa Yehuda, Rina Avner, Lior Marom, Shahaf Zach (area supervisors), Boris Babaiev, Omer Sergey,

Dana Kats, David Dann, Boaz Gross, Sivan Einhorn, Shatil Emanualov, James Boss, Edo Koch, Keren Ras, Shanni Amit,

David Frisbi, and Katia Sonka (assistance area supervisors) Amitai Achiman and Carsten Kettering (Administration), Omer

Sergey (team coordinator), Yoav Pharhi (coins), Itamar Taxel (pottery analysis) and Pavel Shrago (photography).

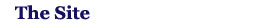

Fig. 1: Aerial view of the site

Fig. 1: Aerial view of the site

Area D1

Located in the southeastern part of the site, area D1 was excavated for the first time in the season of 2005 during which

architectural elements dating to the Byzantine and early Islamic periods were revealed. The small extent of the area

excavated in 2005 (four 5 by 5 meters squares) limited our ability to understand the layout and stratigraphic relationships

of the architecture found. For that reason we dedicated both the 2006 and the 2007 seasons to expanding area D1 to all

directions and to removing the inner balks. Altogether the area excavated reached 350 square meters.

Fig. 2: Area D1 (2007)

Fig. 2: Area D1 (2007)

The earliest features in area D1 are two walls dating to the Iron Age (phase D1–6). As the exposure is very limited at the

moment, it is impossible evaluate the overall plan and the exact date of these features.

To the next phase we attribute a plastered vat and a screw pressing installation (phase D1–4). The vat's floor is mostly flat

and made of plaster except for a small rounded depression covered by a mosaic floor located at the eastern end of the vat.

The installation was attached to a well built wall to the north of it. This wall must have served as a terrace wall and was

built in an earlier stage not yet defined by more finds, and continued to exist in the next phase (see below). Similar

installations were found by Aharoni in the area to the west of our Area D2 (see Aharoni 1964: 16) and under the floor of the

church (see area D4 below). The installations date to the Byzantine period.

For the construction of the next phase (D1–2) the vat was filled with massive stones and earth debris while the screw press

was cut so that they both would fit the new desired floor level. The main architecture feature that belongs to this later

phase is a large courtyard building that dates to the Umayyad and the Abbasid periods (8th–11th

century BC). The building as

|

|

Fig. 3: The plastered vat in Area D1

|

revealed includes a central courtyard paved with massive flat stones. An opening, located in the south east corner of the

court, leads into a subterranean stone-built space located below the courtyard. The space was most likely used for dry

storage although it could have been a cistern.

Two halls were found to the north and to the south of the courtyard. The two were roofed by a vault, and their floor level was

lower in over a meter then the level of the courtyard. The north hall was stone paved while the floor of southern hall was made

of packed earth. Smaller rooms were found to the east and to the south west of the court. A line of stone installations were

found next to the southern and western walls of the southern hall and next to the walls of the southwestern room. The

installations included two stone troughs and three stone shelves.

A massive stone collapse had covered the floors of the different architectural units. The many broken pottery vessels date the

collapse of the building to the Abbasid period or to the beginning of the Fatimid period (10th–11th

century CE).

Area D2

Area D2 is located at the southeastern corner of the site. It was not excavated by Aharoni since a hot water tank that

belonged to Kibbutz Ramat Rahel was located at the spot, situated inside a cement structure. In 2005 the structure was

removed and the area was designated to be a memorial garden for five people killed in 1956 shooting attack from the

Jordanian side of the border on visitors at the archaeological site after it was discovered by Ahaoini and excavated for

the first time in 1954. Prior to setting up the garden we had conducted three weeks of salvage excavation, knowing that

the main features revealed will be incorporated into the garden.

The earliest find in this area is a defense wall dating to the Iron age (D2–5), the eastward continuation of Aharoni's

casemate wall of Stratum VB (Aharoni 1964: Fig. 6, squares M/L-20/23).

Fig. 4: The Iron Age wall in Area D2

Fig. 4: The Iron Age wall in Area D2

The wall is built directly on the natural rock

(combination of flint and chalk), which slopes from north-east to south-west. We were able to trace the foundation trench

which follows the north face of the wall. The trench cuts into the rock. Above the trench, a floor made by a thin layer of

white crushed chalk, approached to the wall and sealed the earth fill of the trench. The few indicative pottery sherds that

were found in the foundation trench all date to IA II, but can not be dated with more precision. The wall is built of large

dressed stones. We were able to follow the wall eastward to a distance of 8.5 meters until it disappeared below a modern

paved road. Aharoni reconstructed a second outer wall running parallel to our wall and three inner partition walls. We

cannot confirm these observations because if the parallel wall did continue eastward, then it is located below the modern

road. It must be pointed out that we found no partition walls.

A well-made thick floor consisting of white crushed local soft chalk rock was found above the Iron Age wall and was

attributed to level D2–3. The floor was exposed in almost the entire area of excavation. Its thickness varies between 20

and 40 cm and is therefore very distinctive. This had made the floor into a stratigraphic base point serving to differentiate

between features that the floor covers, features that coexist with the floor and those that cut through the floor. While

the floor's relative chronology was easy to determine, its absolute date is debatable. In most cases the soil below the

floor did not produce any dateable finds. The only well-dated feature found sealed below the floor is the wall and the

foundation trench described above; both were dated to the Iron Age. Byzantine pottery was found lying on the floor,

but it is clear that at this period the floor was in a secondary use. A few second temple finds that were concentrated at

one spot on the floor furnish at the moment the latest date possible for the floor's construction, but a date in the earlier

Hellenistic, Persian or late Iron Age is still possible.

The upper two layers accordingly belong to the Byzantine and early Islamic periods. The fragmentary walls found should be

connected with domestic quarters found (or ESTABLISHED?) by Aharoni to the west of the area excavated by us (Aharoni

1964: Fig. 1).

Area D3

Area D3 is located in the eastern quarter of the Iron Age palace, in and around the area interpreted by Aharoni to be

the inner-gate of the palace (1964: 25 and Fig. 6). Four squares lined north to south were excavated inside the inner

courtyard and close to the gate. We were hoping to re-expose the courtyard's floor in order to evaluate afresh Ahroni's

dating of the courtyard of the palace. Two more squares were dug south of the inner gate.

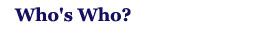

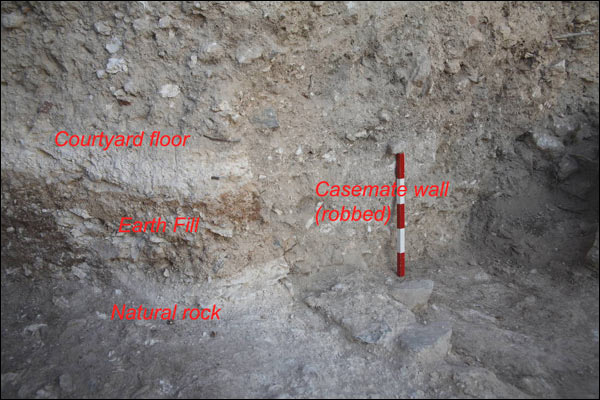

Fig. 5: Section through Iron Age Floor in Area D3

Fig. 5: Section through Iron Age Floor in Area D3

The result of our section into the courtyard's floor confirms the observations made by Aharoni. The floor itself was made

of crushed lime. Its thickness varies and measures as much as 30 cm. Below the floor we found a fill of soil lying above

the natural rock. Apparently the natural rock slopes here from southwest to northeast. The fill and the floor varying

thickness leveled the natural slope and created a horizontal surface. Pottery dating to the later parts of the Iron Age

was found in and below the floor. It is important to note that only one Iron Age stage was found, and the pottery in and

under the floor was of the same type. In this area of the Iron Age palace we found no clues for an earlier 8th century

BCE stratum (Aharoni's Stratum VB).

Fig. 6: Section in Courtyard, 2007

Fig. 6: Section in Courtyard, 2007

A second section was cut south of the 'inner gate' and just by the stone pavement interpreted by Aharoni as the

pavement of the inner gate. Here we found a line of white chalky floor, similar to that of the courtyard described above.

The floor is most certainly located below the stone pavement of the 'inner gate'. Due to the very limited exposure here it

is not possible to determine at this point whether the chalk floor is indeed the same as the courtyards floor. If further

excavations here will prove this assumption, then the stone pavement will have to be to be assigned to a later stratigraphic

stage and the notion of an 'inner gate' will have to be reevaluated.

Area D4 (the church)

Area D4 is located at the north-eastern sector of the site, at the place were Aharoni exposed the remains of a Byzantine

church already in 1954. The church was examined afresh by Aharoni and his fellow colleagues from the University of Rome

in his 1962 season and a detailed report was subsequently published (Testini 1964: 101–106). The church was identified

as the "Kathisma" and small efforts were made in order to preserve its remains. It is important to note that Aharoni and his

team did not excavate below the church floor. In his trail excavations at the site in the year 1984, Barkai, then of Tel Aviv

University, made two sections below the floor of the church, probably in order to expose earlier Iron Age remains. The

results of his excavation are yet to be published.

Following the discovery of the church of the "Kathisma" at the slopes of the site in a rescue excavation conducted by R.

Avner for the Israel Antiquity Authority, it became evident that the church under discussion here is not the "Kathisma." A

re-evaluation of the church in relation to the church of "Kathisma" is thus needed. The 2007 season at the area was

therefore devoted mainly to demarcating the plan of the church and evaluating its structural phases, its date and

consequently its historical and cultural context.

The clearing of the church ground plan from modern debris that had accumulated over the years had affirmed the plan of

the church as it was published by Aharoni and Testini.

Fig. 7: The church (Area D4)

Fig. 7: The church (Area D4)

We had re-exposed the walls of the Apse and the walls of 'room 3'

at the front of the church (Testini 1964: 103 and Fig. 39). Two small sections were made in places were only the mortar

of the mosaic floor was preserved in order to collect coins and other datable material from the foundation of the church.

This material is still being processed and will be reported upon in future publications.

Some hints for an earlier architecture phase of either the church or some other public building were noticed by us in the

sections left in Barkai's square. The most notable of the hints is the remains of floor line sealed by the church's floor. This

earlier floor approaches a large column base which seems to be incorporated into the floor of the church.

To the earliest phase we assigned two large pressing installations made of at least four plastered vats and a two extended

pressing floors. The vats and the floors were sealed by the mortar of the mosaic floor of the church and are therefore earlier.

Walls found below the church's floor indicate that the pressing installation was located inside a built insula, but the exact

plan of this building is yet to be understood.

Area C1

The surprising finds of the plastered pools, drains, and stone built tunnel during the 2005 season had led us to realize that

an exceptional effort is needed in order to understand the water installation found at this area. Prior to the excavation we

had to remove more than 1000 cubic meters of earth, dumped here either by Aharoni or by the military after the 1948 war of

|

|

Fig. 8: Area C1 (looking south)

|

independence. The removal of this modern earth dumps had opened before us the way into enlarging the area of

excavation to the south, west and north. The finds exposed during the 2006 and 2007 seasons made this exceptional effort

worthwhile.

Fig. 9: Aerial view of Area C1 (2007)

Fig. 9: Aerial view of Area C1 (2007)

Three distinctive phases and a number of sub-phases were defined.

The earliest phase (phases C1–6 and C1–5) includes a major change of the natural landscape of the hill and the creation of

an artificially lowered enclosure. The enclosure is surrounded by a steep scarp from three sides: The southern scarp measures

at least 19 meters and is directed from southeast to the west, northwest. The eastern scarp continues for 33 meters and

its direction is north to south. It creates a steep step of close to three meters. When curving out the natural rock here the

mason had to cut through natural crops of flint rock which must have been very hard to cut. The northern scarp is harder to

distinguish and follow, since it was not preserved as nice as the other two scarps. It continues for at least 25 meters in an

east-west direction. Here too the step created by the scarp riches at few point over three meters. Towards the west we did

not find a defining line that marks the end of the enclosure. Since the flattened bed-rock continued westward until the edge

of the area excavated, it could very well be that the enclosed area was left open on purpose to the west and the slopes of

the hill which were terraced. The overall area curved out of the rock and artificially flattened is as much as 1000 square meters!

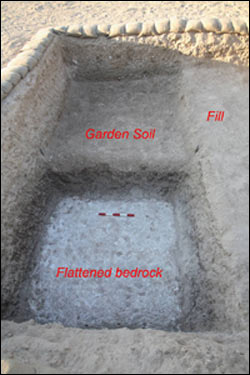

Fig. 10: The garden soil and the flattened bedrock

|

|

As noted above most of the lowered enclosed area was flattened in order to create a leveled and horizontal surface of the soft

limestone rock. On this surface a layer of chocolate-like colored earth, interpreted by us as 'garden soil,' was laid. This soil is

not the natural soil of the site and had to been brought from somewhere else—probably the valley of Rephaim to the west of

Ramat Rahel. Wherever the dark garden soil was exposed it was always around 40 cm thick and laying upon the flattened

bedrock. It has to be noted here that in the 2005 season we had came across similar flattened bedrock surface coated by

'garden soil' in our areas A and B, both located in the northwestern court. Apparently the entire western face of the hill of Ramat

Rahel, all around the palace that was built in the summit, was transformed from a rocky hill into an artificially flat area used for

the planting of a garden.

Other features beside the 'garden soil' found within the enclosure are related to water. In our previous report on the 2005

excavation season we described three plastered pools and one

|

rock-cut tunnel. In the two seasons that followed we exposed more installation that are connected with water and gained better

understanding of the one exposed already.

Rock-cut tunnels: In 2006 we found the continuation of 'Tunnel A', cleaned already in 2005. The tunnel was first cut into the

flattened bedrock and then its side walls were built by stones and plastered. Large rectangular cover stones were used to roof

the tunnel. Previously we reported that the tunnel is made of two sections: the first section is 9.2 meters long in an east west

direction. In its western end, the tunnel makes a 90 degrees turn to the north and continues for 4 meters more until it ends

with a built and plastered wall.

Fig. 11: A picture inside Tunnel A

Fig. 11: A picture inside Tunnel A

In the 2006 season we exposed the outer face of the ending wall and realized it is part of a small

plastered installation that was built into the tunnel and therefore belongs to a later phase (see below). North of the installation

we found the continuation of the tunnel (section C). This section was built of stones and then plastered. It continues for 2

more meters until it reaches the northern scarp and ends.

Fig. 12: The drains and the and the area west of Pool 2

Fig. 12: The drains and the and the area west of Pool 2

It seems that the well built and heavily plastered tunnel (A–C) was created in order to connect the eastern and northern scarp

but at both sides it ends suddenly with no visible outlet for the water. It should be noted that the tunnel follows the outer

contour of pool 2 (see below). The two features were therefore curved and built together.

|

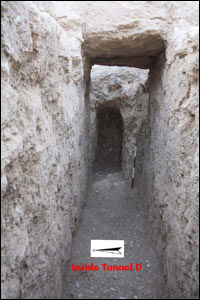

A second tunnel (Tunnel D–E) was found to the south of Tunnel A–C. The newly discovered tunnel shares many similarities with

Tunnel A–C but was built in a much lower quality. The tunnel (D–E) is cutting into the flattened bedrock but it side walls are

built of stones. Only a few cover stones were left from the many that once roofed the tunnel. Section D of the tunnel is oriented

east-west and is 3.25 meters long, starting from the eastern scarp. It makes a turn southward and then continues for close to

fifteen meters, until it reaches the southern scarp (section E). Here too, the tunnel does not lead into a reservoir or other kind

of destination. We are still unable to understand where exactly the source of the water is and what the purpose of the rock-cut

tunnels was. This tunnel connects the eastern and the southern scraps, and it seems that both tunnels were made in order to

hold the water and not to transfer them to any other place.

|

|

Fig. 13: Tunnel D, looking east

|

Plastered pools: In 2005 we reported on finding three pools. Pool 1 was entirely excavated (but not reported or published). The

area interpreted to be 'Pool 3' (south of tunnel A) in the previous report turned out to be part of the flattened bedrock. If indeed

there was a pool here, it was much smaller in scale then previously understood and served as a filtering pool for water running into

Tunnel A. Our greatest progress here was in understanding Pool 2.

Fig. 14: Aerial view of Pool 2

Fig. 14: Aerial view of Pool 2

We continued to clean the earth-fill from within the pool. The

finds from this fill are connected to later usage of the pool and will be elaborated later (below, phases C1–3). We had now

uncovered the four corners of the pool (including the relocation of Ran Morin statue that was placed on the south-western corner

of the pool). The inner size of the pool is 7X7 meters. The north scarp of the enclosure serves as the northern wall of the pool.

Although the natural rock could have served as the northern and eastern walls of the pool, stones were laid against the face of

the rock in order to coat it and create a reinforcing wall. The other two walls were also built of stones. Thick plaster layers were

found on both the inner and outer faces of all walls. We made a section into and below the pool's floor. It turned out that for the

creation of the pool the natural rock was hewn (like in the rest of the enclosure). Then huge thick yet flat stones were neatly laid

upon the rock as a foundation for the floor. A kind of dark cement was used to bridge the gap between the stones. A layer of

cement-like substance was then laid above the foundation stones. This layer was over 15 cm thick and served as the floor of the

pool. Interestingly not even a single sherd or any other kind of datable material was found below the cement floor.

In the 2005 we found one blocked drain (Drain 2) in the southern wall of the pool. The drain carried water from pool 2 into either

small pool 3 or directly into Tunnel A. in the 2006 we found two more exceptionally astatically built drains that led water from Pool

2 westward. Drain 3 begins as a small rock-cut tunnel in the north western corner of the pool, about xx centimeters below the

surface of the pool.

Fig. 15: The curved tunnel of Drain 3

Fig. 15: The curved tunnel of Drain 3

The tunnel makes a curve westward and then by an elegantly shaped step continues upon the built wall that

coats the northern scarp. The later parts of the drain are built by thin worked stones in a very high-quality fashion. Drain 4 is built

in the same manner, about a meters south of drain 3 and 50 centimeters below the surface of the pool. It starts inside the western

wall of pool 2 and continues westward passing above built tunnel C. It should be noted that both these drains were found blocked

by layers of plaster which means they went out of use when in the last days the pool was in use (phase D1–3 below).

The destination of the two drains is still obscure and its understanding is depended on the understanding the most puzzling part of

the enclosure: the area west of pool 2. Here we uncovered a wall built onto the northern scarp. The wall is plastered. To the south

of the wall there is ditch, around a meter thick curved out of the rock. At the base of the ditch we discovered large flat stones,

similar in shape to the foundation stones of pool 2. South of the ditch, the flattened bedrock (this time flint rock) and two small

terrace walls were exposed, one to the south and one to the west (here only a robber trench was found). The area defined by these

two terrace walls and the ditch was the only area in which the 'garden soil' was missing. It seems that the two walls terraced the

soil out of a 'space' the function of which can not be reconstructed. It is clear that the area went through major changes in the

subsequent phases which damaged the preservation of the earlier phases. One reconstruction, admittedly hypothetical at this stage,

is that the ditch was part of a plastered pool of which only the northern and eastern walls survived. The pool was built to the west

of pool 2, in a lower level, and the two decorative drains (drain 2 and 3) must have served for transporting water from the upper

pool 2 into this hypothetical pool to the west.

Undoubtedly the effort needed for the creation of the artificial garden and pools at the west of the site is outstanding. Until now we

have no archaeological knowledge of similarly constructed gardens in ancient Israel. The garden has to be understood in connection

to the palatial building located at the top of the hill to the east and to the north of area C1.

The next three phases include activities that reused and damaged the enclosure and garden. To the earliest of the three phases we

assigned the building of two plastered installations that were built into Tunnel A–C and the terrace wall to the west of it. The first of

the two installations was noticed already in 2005 and numbered as 'Pool 4'. Apparently the pool was small sized and plastered. The

floor of the installation is mostly flat except for a rounded depression at the southeastern corner. The second installation has two small

steps leading down to a flat floor with a rounded depression at its southwest corner. The nature and usage of these installations is not

clear. Similar installation were reported in writing only by Aharoni and dated between the Persian period and the Second Temple period

(Aharoni 1962: 4–5, 27). The creation of the two installations clearly destroyed the underground tunnels and therefore dates to a later

phase. To the same phase we assigned the building of an architectural unit in the southeastern part of the enclosure. This unit was

used the eastern and southern scarp as its wall. Large ashlars stones were robbed from nearby structures and put against the scarp to

support it and avoid its collapse. The northern and western walls of the unit were built of similar ashlar stones, again, reused from

elsewhere. The floor of the unit covered tunnel E. We noted that the floor of the architectural unit was laid after the cover stones of

tunnel E were robbed and therefore concluded that the tunnel went out of use at the time of the construction of this unit. Also important

to notice is that the northern wall cuts through the 'garden soil' and therefore later. The architectural unit was violently destroyed and

few pottery vessels that date to end of the Persian period and the beginning of the Hellenistic period were found lying on the floor. This

pottery assemblage helps in dating the construction of the architectural unit to the Persian period and the earlier features such as the

garden and tunnels to an earlier chronological stage, probably the late Iron Age, the period to which the palace and fort discovered by

Aharoni date. It makes good sense to date the palace and the garden to the same building effort. This assumption is further supported by

the high percentage of Iron Age pottery found in the earth layers above the garden.

Another architectural unit found built into the enclosure is a lime kiln found to the south of pool 2 and Tunnel A. The kiln is made of a

rounded contour and is built of small field stones. A very distinguished burnt soil colored red was found inside the kiln. Outside of the kiln

we found a dark ash layer. These layers, like the kiln itself were all lying atop the 'garden soil.' A white layer of soft lime was found in

the fill inside pool 2. Apparently the plastered pool was re-used at this stage for melting the burnt chalk stones from the kiln by soaking

them in water. This must be the reason why all the drains were found sealed by layers of plaster that prevented the water from

dripping out of the pool. The kiln was dated by pottery associated with it to the Hellenistic period.

The latest phase that damaged the enclosure in this area is a huge earth fill that covered the entire area. This fill, which seems to be

intentional, completely buried all the features described above. Its nature was very homogeneous and it contained a rich collection of

pottery shards, the latest of them dating to the second century BCE, arrowheads of the same chronological horizon and a large corpus

of stamp handles, of the kind typical to the Iron Age, Persian, and Early Hellenistic periods.

The earth fill buried the enclosure and leveled it to the surface of the area to the east and north (the summit of the site). From that

time onwards the area was in the outskirts of the settlement. Most of the features found from these phases, dating to the Second

Temple, Roman and Byzantine periods, are agricultural installations that were cut into the natural bedrock that surround the enclosure.

A vat for winepress was found at the northeastern corner of the enclosure. The pressing floor of this vat was probably built above Pool

1. Many subsurface agricultural installations and some burial tombs were found carved into the rock to the east of the enclosure, among

them a cave with columbaria. These features are reported upon in more length below. Architectural remains from these phases include

a well constructed stone podium built into the southwestern corner of the enclosure. Pottery and a number of tessera stones collected

from its foundation trench prove that the podium, maybe the base for a small tower, was built in the Roman period or later. A wall built

of huge boulders lined along the northern scarp marks the latest phase at the area. This boulder wall was built by the Israeli army

between 1948 and 1967 in an attempt to support the line defending position built above and north of the boulder wall.

Area C2

Area C2 is located to the north of area C1 and above the lowered enclosure. In 2005 we reported on our attempt to retrace the plan

of the Iron Age walls exposed already by Aharoni (1964: 49). In 2006 we did not excavate in this area. In the 2007 season we return

to this area hoping we will be able to connect the palatial architecture dated by Aharoni to the Iron Age with the newly discovered

garden to the south and to the west. Unfortunately the bed preservation and the military trenches that cut through this area hindered

any possible connection between the two architectural units. We did mange to re-expose the main north-south wall of the Iron Age

palace (wall west of locus 729 on Aharoni 1964: Fig. 6). Now that we proved that the southwestern corner of the Iron Age palace was

not where Aharoni claimed it was, it seems that this wall should be seen as the closing wall of the palace, separating it from a

projecting fort located to the west of the wall. A huge flat stone which constitute part of the wall may have served as a royal threshing

that led from the palace to the east into the projecting fort, composed of two towers.

Apart for cleaning the previously exposed Iron Age architecture, we also dug a huge subterranean space that was cut into the natural r

ock, located just east of the above described wall. The space was originally cut for a Jewish ritual bath ('mikveh'). The rock-cut walls of

the bath were coated with decorated plaster with a unique tree-like design. A line of steps led down into the bath. In a later stage,

dating by an abundant number of finds to the Byzantine period, the steps were curved out and the space was covered by vault roof.

Aharoni reported finding similar vaulted subterranean spaces at other parts of the site (for example Aharoni 1964: 14).

Fig. 16: The decorated plaster in the ritual bath

Fig. 16: The decorated plaster in the ritual bath

Survey and excavation of underground spaces

During the 2006 season of excavations, a team from the Cave Research Unit (CRU) at the Hebrew University was invited to perform a

survey and mapping of ancient subterranean spaces. The team was headed by Roi Porat and Uri Davidovich which were assisted by two

CRU members. The field work began by making a general survey of the "southern hill" of the site, bordered by Aharoni's excavation area

to the north, Area D of the current expedition to the east, the parking lot and modern road to the south and south-west, and Area C1

to the west. The survey's goal was to trace all the currently exposed openings to subterranean spaces, in order to better understand

the subterranean activity in this area. Ten such spaces were found, all of them artificially hewn. The underground spaces include: two

water cisterns, two Jewish ritual baths, a columbarium, two rock cut tombs and three spaces that could not be defined. The cave with

columbaria and the cave with the ritual baths were chosen for further excavations, which were carried out during the 2006 and 2007

seasons.

|

The ritual bath excavated is shaped as a stepped subterranean rectangular cave, measuring c. 3X2 m. It contains 3 wide steps, and a

slightly wider bottom. The original hewn passage leading into the ritual bath is sealed by later debris, in which few steps were shaped,

probably in order to use the space in a later period. While cleaning the accumulation found inside, it became clear that the ritual bath

was open in the last decades, since beer bottles and bags were found at the bottom of the accumulation and below large fallen stones.

It seems that it was cleaned by one of the former expeditions to the site, or in another unknown occasion. In any case, the ritual bath

is now cleared down to its bottom, and constitutes another nearly complete example, and seventh in number in Ramat Rahel, of this

typical Second Temple Period Jewish ritual bath. It thus helps to estimate the perimeter of the settlement in this period, a relatively

under-represented time-span in the above-ground architecture of Ramat Rahel.

|

|

Fig. 17: A Jewish ritual bath west of area D1 after entail clean up

|

Fig. 18: A columbaria east of Area C1

|

|

The excavation in the columbarium area resulted with the appreciation that the subterranean complex is much more elaborate than

previously known. At least two ancient entry-ways into the complex were found, one of them thought to be an opening into a different

cave in the preliminary survey. Two more chambers which contain columbarium niches were found, as well as additional two dividing

walls within the subterranean zone. From a relative chronology point of view, we can define at least five different phases. Nevertheless,

regarding the absolute dating of the various elements and phases, nothing can be stated with certainty except for the accumulation

inside chambers D and E after they went out of use. Though the pottery assemblages still demand further study, it is safe to determine

that the columbarium complex functioned before the Late Roman period and possibly even before the end of the Second Temple period,

since pottery, stone vessels and glass

|

objects dating to the latter periods are found in the above-mentioned accumulation. The ancient hewing (chamber F) found below

chamber A of the complex should be dated to the Hellenistic period, if not earlier.

|

|