Donors

Barbara Sieratzki was born in Cracow (Poland). After the German invasion, she escaped to Prague and later to Bratislava, and Budapest, and completed high school in Hungary using a Christian ID. She was arrested in June 1944 and transported to Mauthausen, together with her mother Gusti Tennenbaum, from where they were liberated by the Russian Army in 1945. Barbara briefly returned to Hungary and studied at the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Budapest but soon, for financial needs and her natural talent for languages, became an interpreter for the Jewish Agency and subsequently a liaison officer to the British Army in Bergen Belsen.

In 1949, Barbara married Heinrich Sieratzki and they together built a new life and raised a family in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, working first in textiles and subsequently in the property field. After her husband’s early death, Barbara managed the business on her own.

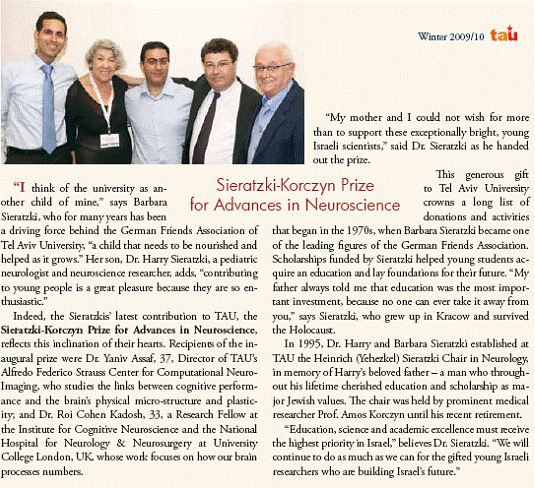

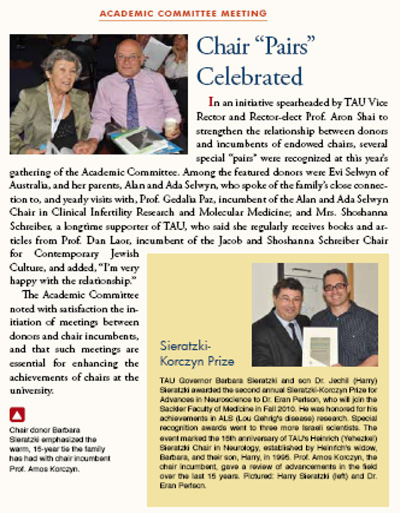

She played a major role in the establishment of the Friends of Tel-Aviv University in Germany and was in 1995 made an Honorary Fellow of Tel Aviv University. Barbara, in 1995, founded the Chair in Neurology at Tel-Aviv University, named after her late husband, and in 2009, together with her son, Harry, the Sieratzki Prize for Advances in Neuroscience. Barbara lives in London.

Harry (Jechil) Sieratzki was born and raised in Frankfurt am Main. He studied medicine in Strasbourg and in Giessen (Germany) and worked as a Physician and Researcher at the University of Frankfurt, Mount Sinai Medical Centre New York, New York State University, Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Bristol, and Hammersmith Hospital (London). His early research was on diseases of the liver and the biliary system but he subsequently moved to brain studies. His work on hemisphere functions and mother-infant communication has received wide interest in the medical and non-medical world.

IN MEMORY

Heinrich (Yehezkel) Sieratzki (From a speech given at the 1995 inauguration of the Heinrich (Yehezkel) Sieratzki Chair in Neurology)

My father was born in Piortrkow Trybunalski in Poland, a regional centre with a population of about 80,000; one third was Jewish. It was not a shtetl, but a place where the roots of history and identity were strong. The family owned a textile store, was not rich, but highly regarded for being charitable. Their house still stands, but there are no Jews left in Piotrkow. He was the second oldest of 6 children and is shown here with one of his younger brothers (Moniek) and 2 sisters. At age 14 years his father fell ill and died of a stroke; he had to abandon his school education to run the textile store and support the family. Throughout his lifetime he cherished education and scholarship in all fields.

Close to his roots, he saw great traditional and humanistic meaning in Jewish learning. His understanding of Jewish life meant to maintain the memory of his vanished world. As the President of the Chevra Kadisha in Frankfurt, he was asked why he, a successful businessman, was involved in this last and so burdensome service for the dead.

He said: "I do it for those who did not have it”.

He had a particular interest in the story of Job, the man whose belief in the justice of God does not waver even when subjected to grave disaster. He saw life in the first place not as a chase for success, but as a challenge for moral behaviour and dignity.

There are no rules and rituals for this challenge, and indeed my father's general principle of life was not to be rigid. He had what one calls in Yiddish a "schmeichel", a warm smile and a good word. He liked to laugh, to tease, to dance, to live well.

When the war ended, my father returned to Piotrkow, but life was no longer sustainable there. He moved to the zones occupied by the American forces and finally to Frankfurt. He was a good merchant, and he knew a good deal when he saw one.

More than this, he even succeeded in getting my mother to marry him…

The post-war period in Germany was a time of rebuilding. Who can say if life could be rebuilt? I can only say that my father and mother, having survived the Shoah, wanted to make something of and with their lives. Happiness and satisfaction do not come on a doctor's prescription; sometimes they come where they are deserved, sometimes they come against the odds.

The ingredients: a family, a home, health, and "parnassah" came together and with great care and "kavod", my father would make sure that my mother's mother, Gusti Tennenbaum (on the right) would feel as the spiritual head of the family.

The success in his enterprise came as well. In Frankfurt, he again had a textile store, with the privilege to teach apprentices. From small beginnings, his projects became bigger, but he was not after those trophies that glorify a man's ego. He always knew that there were more important things: life with enjoyment, the commitment never to forget those who were no more... the world of learning, beginning with the never-ending curiosity of cheerful children, whom my father loved, to the illustrious levels of scholars and scientists (Harry Sieratzki).

IN THE TAU PRESS