Return to the radiologic techniques menu.

Return to the radiologic techniques menu.

Return to the radiologic techniques menu.

Return to the radiologic techniques menu.

X-rays were first discovered by Dr. Wilhelm Roentgen in 1895. They are a form of electromagnetic radiation with a very short wavelength, much shorter than visible light. Unlike visible light, which is reflected from most objects, x-rays can penetrate through objects. By placing a film sensitive to x-rays behind an object--or patient body part--and directing a beam of x-rays toward the film, an exposure is made. The exposed film is developed to a positive print in which denser, more radiopaque tissue or objects appear brighter, while less dense materials are more radiolucent and appear darker.

How dark or bright tissues or materials appear with x-ray exposure depends upon:

Composition

Thickness

Exposure

The composition of substances gives rise to the degree of density they have against x-ray penetration. The most dense material is lead, which can stop x-ray penetration. A contrast material such as barium sulfate is nearly as dense. Bone that contains calcium is also dense, but not completely radiopaque. Of the soft tissues, muscle is more radiopaque than adipose tissue. The density of muscle is about the same as blood and normal liver parenchyma. Adipose tissue is not quite as radiolucent as air, so lungs are darker than the chest wall.

Any given tissue will be more radiopaque if the x-ray beam has to traverse more of it, so thickness is a factor. For the same exposure, a phalangeal bone of the fifth finger appears more radiopaque than a femur. By rotating the body part to be examined, differences in tissue density and thickness can be exploited to highlight the structures present. Standard views, including posterior-anterior (PA), lateral, and oblique can be obtained and compared.

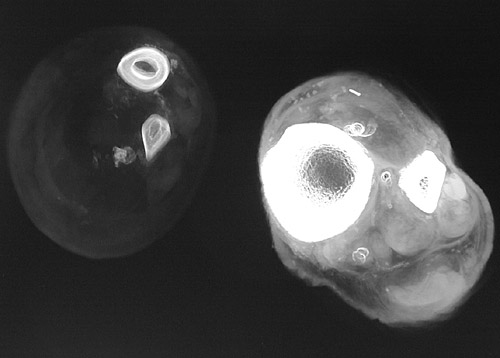

The amount of x-ray exposure can be varied. In general, to reduce radiation exposure to the patient, the lowest dose of x-radiation possible is used. The amount of x-ray exposure is a function of time and intensity, both of which can be varied. A longer time of exposure or a more intensive beam of x-rays will result in more radiolucency. Films exposed in this fashion are "overexposed" or "overpenetrated." Conversely, film exposed for a shorter time or with a less intense beam will appear "underexposed" or "underpenetrated." The image below compares two different degrees of penetration of the lower leg in cross section with tibia and fibula.

The amount of x-radiation to the patient is also limited by decreasing the size of the body area exposed. The beam can be narrowed and the film size reduced to fit the needs of the situation. Hence, dental x-rays are only a few cm in size to view a few teeth per exposure. The largest film size is usually needed to produce a chest radiograph (roentgenogram).

Chest radiographs are generally taken with a posterior-anterior (PA) x-ray beam in patients who are healthy enough to stand and position themselves in front of the film. An AP view is necessary for ill patients using a portable x-ray device that can aim the beam down through the bedridden patient to the film behind. Another view often included for evaluation of the chest is a left lateral x-ray. The views utilized depend upon the body region and the purpose.

Normal PA and lateral views of the chest are shown below. Note the darkness of the lung parenchyma (mostly air) contrasted with the brighter bone of the ribs. The chest wall musculature is a medium grey.

X-rays have many non-medical usages. Radiographs can be used to detect flaws and fatigue in metals forming structural components in airplanes and other vital equipment. In airport terminals, baggage is subjected to x-ray screening in order to detect items that should not be on board. An example of a radiographed handbag is shown below. Would you let this passenger on the airplane?